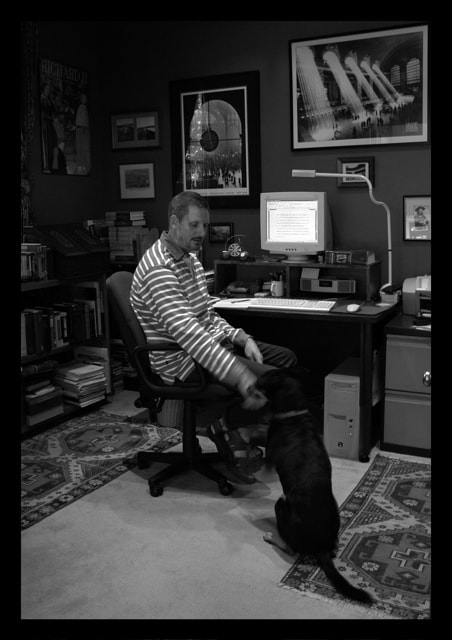

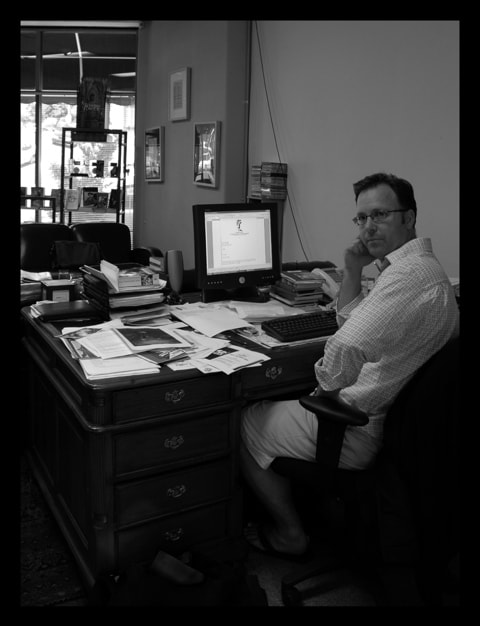

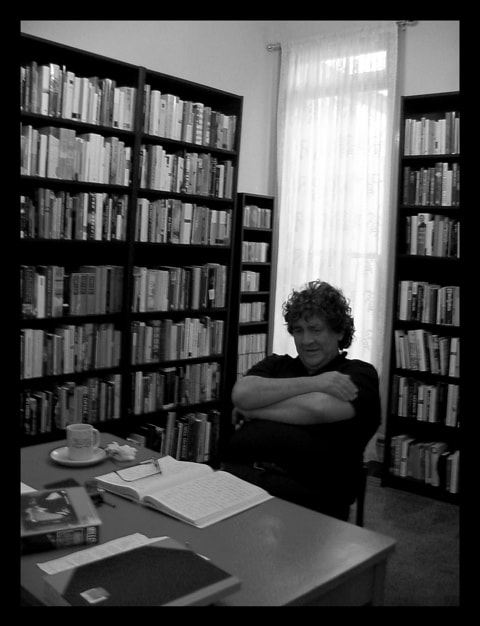

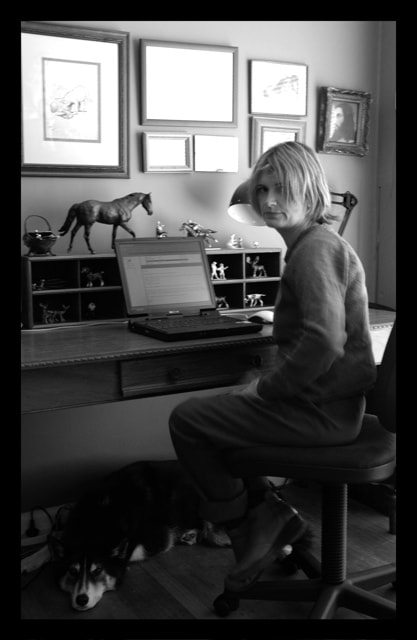

In 2005 I was studying my MA in writing and had been working at THE AGE newspaper for 5 years, when I had the idea that would be my first published book: Literati: Australian Contemporary Literary Figures Discuss Fear, Frustrations and Fame (John Wiley & Sons, 2005). What followed were discussions with 21 Australian literary figures.